For illegal immigrants, a small procedural change is having a big impact on getting a “green card”

SPRINGFIELD, Va., 9 March 2014 – Eva hugged her son, trying to reassure him. William was young – just 13 years old – and still in school, so he had to stay behind. Though still a boy, he was old enough to understand what was happening, and he buried his face in Eva’s long brown hair. He didn’t want his mother and baby sister to leave. Most of all, he feared he would never see his father again.

“We have to put our faith in God,” said Eva.

She was returning to El Salvador, a country she had not seen since she was 16 years old. Although Eva entered the country illegally years ago as a child with her parents, she and her family became U.S. citizens in the mid-1990s. But then she married Oscar, also a native of El Salvador, who entered the country illegally in 2001 and who has not been able to change his status since.

Once an immigrant becomes unauthorized, such as by overstaying their visa or entering the country illegally, there is no path to legalization while that person remains in the United States. Even if they have someone to sponsor their application for legal permanent residence status – a U.S. citizen spouse or an employer, for example – they are still required to leave the country, collect their “green card” while abroad, and reenter legally.

Eva decided to accompany Oscar back to their country of birth while he completes the last steps of his application to live legally in the United States. This process includes an interview with an immigration officer at the U.S. consulate in El Salvador. Because they are currently working to legalize Oscar’s status, Eva asked that their last name not be used.

But until recently, a trip abroad wasn’t the only significant hurdle to getting a green card. Many illegal residents first would have to obtain a waiver for the “three- and 10-year bars.”

Passed by Congress in 1996, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act states that immigrants who reside illegally in the country for six months to a year and then decide to leave are barred from returning to the United States for three years. Those who remain for more than a year are barred from returning for 10 years.

In certain circumstances, unauthorized immigrants can request a waiver from the government from the three- and 10-year bars, but their application must be submitted and adjudicated while they are abroad.

“Because they are barred from changing status within the United States once they are undocumented, they would have to leave not knowing whether their waiver had been approved or not,” said Matthew Kolodziej, a legislative fellow with the American Immigration Council.

“Sometimes those waivers would be denied,” Kolodziej said, “and that person would have effectively deported themselves and be banned from the United States because they left in the hopes of getting this waiver.”

The possibility of being separated from family members for an extended period of time kept many unauthorized immigrants from completing their green card applications.

“Up until now, we have not been able to do much of anything because of this law,” said Eva.

More than a year ago, Eva and Oscar began working with a lawyer to apply for a waiver, but stopped when they realized there was no guarantee Oscar could return. The risk of long-term separation was too high. They decided it was better for their family if Oscar remained in the country illegally.

There is an additional unintended consequence of the 1996 law: the three- and 10-year bars actually may be encouraging the growth of the unauthorized population.

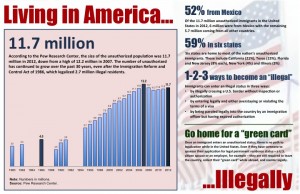

There are more than 11 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States today, according to Jeff Passel of the Pew Research Center. Between 1996 and 2012, the unauthorized population grew by more than five million.

“There are a lot of people who argue that if we didn’t have the three- and 10-year bars, we would not have 11 million people here illegally because they would have found other ways of adjusting,” said Muzaffar Chishti, director of the Migration Policy Institute’s Office at the New York University School of Law.

“Before 1996, you had to be terribly unlucky to be picked up by immigration services,” said Chishti. “We almost did not enforce the immigration laws.”

Unauthorized immigrants would remain in the country for years, eventually finding an employer or marrying a U.S. citizen who would then sponsor their green card applications. After a quick trip home, they would reenter the country as legal permanent residents.

“So it was almost like a revolving door. That ended with the three- and 10-year bars,” said Chishti.

Many unauthorized immigrants opted to remain in the United States rather than apply for a waiver because there was no guarantee of return, even if they had a sponsor. This kept people who would have normally obtained a green card “frozen in their present legal status,” said Chishti, resulting in a large unauthorized immigrant population.

In March 2013, the Department of Homeland Security issued a new rule allowing unauthorized immigrants who were immediate relatives of U.S. citizens to apply for and obtain a waiver while they were in the United States, before they depart to attend their immigrant visa interviews in their home countries.

The new policy, first proposed by the Obama administration in 2012, is designed to “reduce the amount of time families spend apart during the application process, and remove separation as a deterrent for those who wish to pursue an application for lawful permanent residence” but require a waiver, according to an article coauthored by Chishti.

While comprehensive immigration reform is still needed, this one procedural change is a step in the right direction, said Kolodziej.

“The stateside waiver adjudication policy is very good for the undocumented population. This removes an enormous risk that waiver applicants faced before.”

“No one prefers to be an illegal alien,” said Chishti.

Kolodziej agrees. “The vast majority of undocumented immigrants would prefer coming to the United States legally.”

And many would do whatever it takes to get that green card.

Before their trip to El Salvador, both Eva and Oscar worked extra hours and at night to scrape together enough money to pay for airfare, the expenses associated with the application process, and being off work for a month. And all this in addition to the thousands of dollars they have already spent on legal fees.

“It’s a hard process,” said Eva. “In the middle of everything, we have no idea really what to expect.”

Recently, Oscar and Eva found out that Oscar had received a waiver. He now has permission to return after leaving the country, but there is still no guarantee he will get his green card. He has yet to complete his medical examination, background check, and final interview with an immigration and naturalization officer in El Salvador.

But Oscar is hopeful, and looking to the future.

“I am very grateful for the opportunity this country has given me,” said Oscar through an interpreter. “I have met so many people who have treated me so well. I feel this is my country, and my best years have been here. It’s not only about getting a green card, citizenship is my ultimate goal.”

“For me, the next step would be to become an American citizen,” he said.

Elizabeth M. Grieco

American University

March 9, 2014